Position Statement: Releasing Companion Birds

At World Parrot Trust, we sometimes receive questions from individuals who feel that their companion birds might be better off and happier if they were returned to the wild. While we applaud this desire, we strongly advise against release for the sake of the individual birds's welfare and for the well-being of wild populations. Returning parrots to the wild can be done successfully and increasingly so, but only when carried out under well-managed programs, most of which cannot be undertaken by individual parrot caregivers.

Birds that have been raised as companions are rarely able to survive a life in the wild

What works and what doesn't

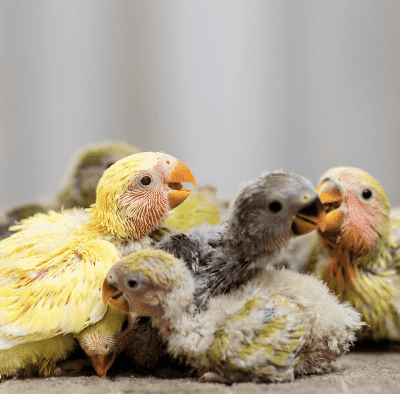

In our direct experience with releasing parrots, we have observed that the birds with the highest probability of survival are those that have been hatched in the wild and only recently been captured, or those birds that have been bred in captivity in carefully managed environments and properly prepared for a life in the wild.

Formerly wild birds retain many important skills needed for survival, such as recognizing wild foods and knowing how to interact with others of their species. Wild birds have well-developed patterns of behaviour and are able to successfully participate in complex social hierarchies that allow them to interact as a group, which helps them to successful evade predators, find food and otherwise prosper.

By comparison, many long-term companion parrots were born in captivity (sometimes for generations), and have been living closely with people. They are often kept alone, and rely heavily on their caregivers to provide the necessities of life (food, water, shelter, companionship and enrichment.). The skills they have acquired to become good companion birds are often the exact opposite of what is needed to ensure their survival in the wild.

When companion parrots like this are released, they face the very real pressures of starvation, getting eaten by predators, encountering extreme weather, being poached or hunted and being placed in an environment that is completely unlike anything they have experienced before. If they are released alone, the likelihood of their survival is further lowered. Only a very small percentage will survive, unless they undergo extensive preparation and conditioning on how to survive and thrive. For these reasons, we strongly advise against returning companion parrots to the wild unless under very special circumstances.

feeding stations at Rio Abajo Aviary

© Tanya Martínez

© Ed-Ni-Photo, Getty Images

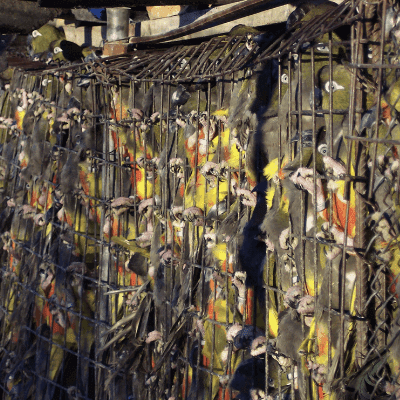

Permits and disease risks

Most international transport of parrots is governed by CITES, an international convention intended to monitor these activities. In order for a bird to be returned to its country of origin, it must be accompanied the appropriate paperwork, in addition to health profiling and other assessments. Obtaining the required permits is often a complex and time-consuming process.

A larger concern for birds that have been in captivity for a lengthy period of time, even those under the best of care, is that they may have been exposed to diseases that may not be found in wild bird populations. Releasing a bird with undiagnosed disease may further endanger wild populations, particularly already endangered ones. Therefore, only birds that have been carefully screened for disease and quarantined before release should be considered as suitable release candidates.

What are the alternatives?

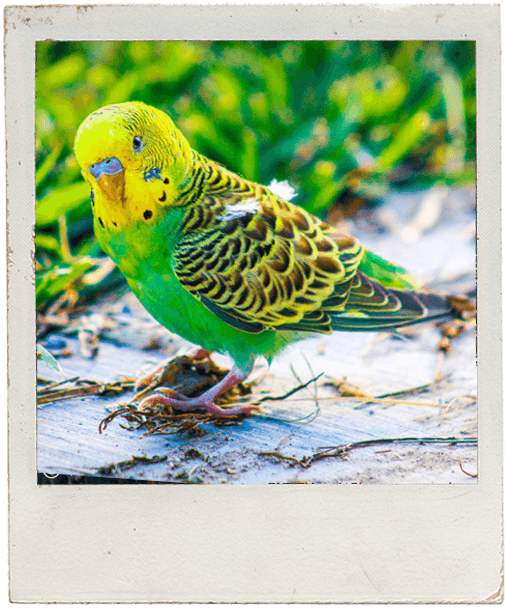

In almost all cases, we strongly encourage caregivers to provide their feathered companions with the largest flight area possible, a wide variety of stimulating enrichment items, companionship, and a healthy diet. While captive parrots clearly can't lead the same life as wild parrots, they are safe from predators, starvation, trapping and violent weather events, and can be provided with a long and interesting life.

For caregivers who are no longer able to care for their feathered companions, we recommend placing the bird with another caring family, making it available for adoption, or placing it in a zoological institute or dedicated bird sanctuary where it can be well-looked after. Tamer birds in public facilities can often become terrific ambassadors for their species, and aid in educating the general public about the plight of all parrots in general.

the UK Kiwa Centre © WPT